Su Tung-p’o, the great eleventh century scholar, painter and connoisseur wrote of his friend’s work,

When I savour Mo-chieh’s poem’s, I find paintings in them; When I look at Mo-chieh’s paintings, there are poems in them. (1)

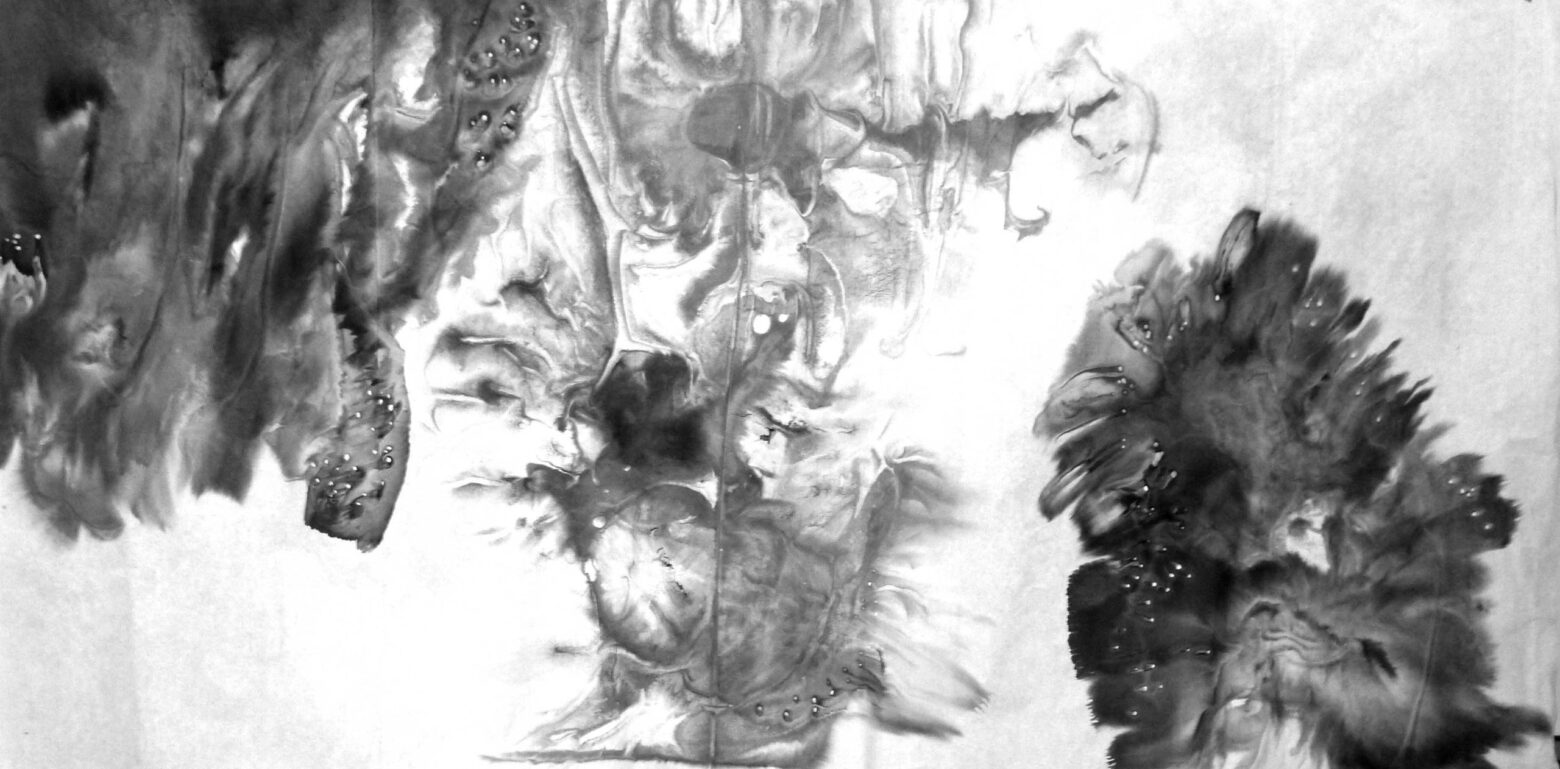

In the work of the twenty-first century landscape painter, Ming Ren, one finds poetry as well. Similar to the expressive work of Mo-chieh and of his compatriot, Su Tung-p’o , Ming Ren’s painting goes beyond the uttered word or brushstroke to portray the poetic qualities of nature in an extraordinarily broad manner. Michael Sullivan has written that Su Tung-p’o and his colleagues were revolutionaries whose idea was “that the purpose of painting…was not to depict things…but to express the painter’s own feelings.”(2) Ming Ren similarly creates fields of imagination in which his pigments migrate, separate and merge to create compositions whose randomness establishes organic parallels to observed nature. Ming Ren’s landscapes are assumed by the viewer rather than created as such, in a partnership between artist and his audience not unlike that of Su Tung-p’o and Mo-chieh. Ming Ren’s spare work entreats the viewer to speculate about the scale, point of view and direction of his paintings. He projects moods as visual ideas through his poured and splattered paint, and through his strict economies of medium and white space within the field of his painting.

Ming Ren’s work both follows this centuries-old revolutionary moment in Chinese landscape painting, and breaks with it, creating a new “post modern” perspective on the history of Chinese painting. One can find few references to traditional Chinese painting techniques or even visual reference points in his work. Ming Ren abandons his viewers to set their own imaginative course within his broad canvasses, forcing them to compose their own “visual poetry.”

The conversion of image and form from written to visual language in the history of Chinese painting is through a migration from calligraphy to brushwork. Each creative form of expression bears a symbolic reference to nature within the realms of imagined and perceived nature. One cannot say which form of expression came first – or which influenced the other more. Ming Ren’s paintings have evolved in somewhat the same manner, although, as we shall later see, his “writing” is in the form of literal depictions to twentieth century political imagery.

Su Tung-p’o and subsequent Zen masters freed Chinese painting from literal interpretation of nature, and to focus it on the internal emotive perspective of the painter and viewers themselves. To this form of painting, Ming Ren’s current work most closely relates. The rest of the history of Chinese landscape painting is characterized by formal conventions of composition and brush painting technique that Ming has rejected in favor of a more abstract, contemplative formula. The homage that Chinese art has paid to its past, even through the Social Realist era of the mid-twentieth century, has been absorbed by Ming Ren. It has not been put aside, but reformulated into a “post-modern” concept of both the form of art and the subject.

That Ming Ren has come closest to the Zen form of art is curious but reassuring. Straddling two centuries of art himself, in an era of great contact between China and the West, Ming Ren has been able to learn from many sources, some of which are in direct conflict with each other. Western modern art during the twentieth century set canons of difference; artists stepped over the art of their peers and predecessors, rejecting the form and techniques, in an effort to be new and different. Artists of the East were required, in many cultures, to follow a strict adherence to the subjects and styles of past periods in their history. Ming’s art has now matured to the point of his complete absorption and respect for these previous forms while projecting his own independent creative spirit. He is therefore a totally twenty-first century artist: internationally connected and influenced, bridging Eastern and Western imagery, ideas and techniques. In reaching backward to some of the earliest, most indigenous Chinese Zen sensibilities, Ming Ren has enabled himself to be free, yet related to the emotive content of the art of the past. His pathway to this accommodation and freedom was not easy.

Ming Ren grew up in a family of professionals – scientists by education. They did not encourage his childhood interest in art. By chance, as a teen-ager during the full impact of the Cultural Revolution, Ming Ren was invited to paint a large political signboard in the Hangzhou city square. He thinned the paint he had been given, and poured the excess off into containers for himself. Secretly and against the wishes of his parents, he began to make his own paintings. In time, with youthful courage, he showed his work to some local artists. Recognizing his talent, they took him under their wing. Some of these artists were among the faculty at the China Art Academy in Hangzhou, and they encouraged him to apply there. He was one of ten students admitted during that year from over 12,000 applicants. In the early1980’s when he was being taught at the academy, the Cultural Revolution was ending. The Chinese brand of Social Realism, through which Ming was trained academically, still demanded adherence to official canons of subject, proportion and technique. The source of this style was Russian instruction, from which Ming Ren’s teachers derived their curriculum as well as their own training. But during this time, the academy began to open its doors to artists and faculty from the West. For the first time, he and his fellow students were able to see the art of the West. Ming Ren became determined to travel and to learn more of the art of the world.

Upon graduation, Ming Ren was asked to stay on as a faculty member, and he worked in the international exchange program at China Art Academy. He received invitations to lecture and teach in the U. S. and elsewhere abroad. He first came to Rhode Island School of Design in 1988, and to the University of California, Santa Cruz the following year. In 1991, Ming Ren received his MFA from San Francisco Art Institute. He also has taught at the San Francisco Art Institute and the College of San Mateo. Currently he is teaching at the City College of San Francisco, and has made an annual teaching pilgrimage to RISD to teach the Wintersession program there. He also has taught at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing.

During this time and even now, Ming Ren ferociously pursues the opportunities to look at contemporary art. Throughout his travels, he regularly keeps in contact with artists and exhibitions that reveal to him new ideas, techniques and materials. He became fascinated with acrylic paints, formerly not available in China. In his first exhibition in 1990, his “post-modernist” style utilized social realist methods to combine Western and Eastern imagery. In 1994, he worked for the artist materials manufacturer, Binney and Smith, and was, as he put it, “overcome by a wide selection of new materials,” which became available to him. Ming Ren and his associate at the San Francisco Art Institute and friend, Jeremy Morgan, experimented with these new materials and learned together how to apply them. This experience “opened his mind,” as he says, to the potential of the acrylic medium, which he began combining with gouache and other water-soluable material. He began giving lectures on these experiments at the China Art Academy, Central Academy of Fine Arts, and the Shanghai Art Academy.

All the while Ming Ren was experimenting with these new materials and supports, he worked to manage their interaction. The liquidity, transparency and opacity of the paint and medium in various combinations and densities, and the relative absorptive receptivity of the grounds on which he poured these materials were a great challenge to him. Happy accidents became doorways to new methods, which after many tries, could be controlled. Through these manipulations, Ming Ren freed himself from painting regulations and rules that he had mastered, but to which he had not totally submitted himself. He was now ready to migrate from a period during which he was linked to past traditions of Chinese art to develop work beyond these connections. Ming has come now to the happy resolution that the combination of traditional and contemporary art is beneficial, and that modern technological advances in media and support systems help advance his art with due respect to the past.

His paintings infer landscapes; they are most often secured onto scrolls in Chinese traditional fashion. As they are rolled open, the very sequence of their revelation creates a sense of expectation as with Chinese landscape paintings of old. They are imposingly large open compositions, and impressive in their scale-less format. No “details” that could give the viewer a sense of distance or place are evident. These paintings imply vast mountains and valleys, rivers and pools. But they also suggest microcosmic spaces into which we gaze from close range. The only indications of size and comparative location are the drops and speckles of pigment that float among the poured painted surfaces. The flowing aspects of his compositions are both restful and energizing, in that they hint at vast spaces beyond the boundaries of the ground on which they are painted.

These paintings are sections of a larger reality, drawn by Ming Ren to our attention for a studied view. Without our twenty-first century experience of images projected from space, we would not be able to relate to the sky-high impressions of mountainous landscapes that Ming creates. But we could imagine in a dream the impact of these vast spaces – flying through space in our mind’s eye. To attach these experiences to a dream brings us full circle to Su Tung-p’o, who saw poetry in the images of his friend.

Like the work of Su Tung-p’o and the other Zen-influenced thinkers, artists and writers of their time, Ming Ren’s paintings describe alternative realities that are more cerebral than actual. They inspire the viewer to imagine other worlds, taking us from what we know to other places that are in the end, just paint and paper or canvas. Ming Ren’s works of art serve as pointers toward deeper understandings since they are paradoxically puzzles of space and locale toward which we have no perspectives, other than inner ones, from which to solve them. In these conundrums, literal truths become metaphysical ones, taking us from what we know to new places of artistic pleasure and meaning.

Roger Mandle

President

Rhode Island School of Design

September, 2006

________________________________________________________

Footnotes:

1. Michael Sullivan, Symbols of Eternity: The Art of Landscape Painting in China, (Stanford, California, 1979), p. 81.

2. Ibid, p. 80.

roger mandle

A cum laude graduate of Williams College, Mr. Mandle holds a MA from New York University and a Ph.D. in Art History from Case Western University. He was appointed President of Rhode Island School of Design in 1993. As an educator, art historian, and leader of major cultural institutions, he has been a nationally known figure in the field of education in the arts and humanities for the past twenty-five years. After serving as the Associate Director of the Minneapolis Museum of Art, he was Associate Director and then Director of the Toledo Museum of Art. He next moved to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., where he was Deputy Director and Chief Curator from 1988 to 1993. In addition, Mr. Mandle served as a member of the National Committee for Education Standards in the Arts, for whom he was a co-author of education Goals 2000: Standards in the Arts. He was appointed as a member of the National Council on the Arts by both President Reagan and President George H. W. Bush, and served for eight years. He is currently a member of the Executive Committee of the Ambassadors for the Arts, appointed by former President Clinton. He was Chairman of the Executive Committee of the American Federation of Arts; Vice President of the American Association of Museums; and a member of the Association of Art Museum Directors. He has been a member of the Board of the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts. He is a member of the Board of Directors of the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design. He currently serves on the Board for the Alliance of Artists Communities, and on the Board of the Newport Restoration Society, of which he is Vice-chair. He was also chairman of the Rhode Island Independent Higher Education Association and a Board Member of, the Providence Foundation, the Rhode Island Children Crusade, the Advisory Board of Perishable Theater, and Providence WaterFire. He is a member of the Program Committee of RIPEC. He was also Vice-chair of the Advisory Board of the John Nicholas Brown Center for the Study of American Civilization. Mr. Mandle is a published scholar and teacher on the subjects of aesthetics and Dutch art.

Mandle has served as a member of the board of directors of Trustcorp, a bank in Toledo, Ohio (now merged with Key Bank, Cleveland) and Cranston Printworks, Cranston, R. I. He has also been a member of the board of directors of Deepa Textiles, San Francisco, California.